Who needs fast glass when you have high ISO?

I've seen a few comments from some photographers stating that with the good high ISO performance from current cameras, there's no need to spend money on fast glass anymore. (If you're wondering what fast glass means, it means lenses with a large maximum aperture like f/1.4 or f/2.8, you can read more here: What does Lens Speed mean?)

In this article I want to take a look at this argument, and see if there is any truth in the statement.

Most new cameras can indeed achieve very high ISO levels, ISO 12,800 was unheard of in the days of film and early days of digital photography. But today we have cameras going even to an equivalent of ISO 102,400! The top ISO levels still tend to be a quite noisy. But lower levels like ISO 6400 can give very clean, usable results.

Sony #A7s High ISO 6400 Test #HK #HongKong #Asia #Cityscape #City #VictoriaHarbour #Harbour #prosperity #skyline by Pasu Au Yeung on Flickr (licensed CC-BY) - taken using ISO 6400 with the Sony A7s camera, released 2014

Using a higher ISO setting boosts the sensitivity of your camera to light, allowing you to get usable images in lower light levels. In the same way, using a large aperture setting on your lens lets more light into the camera, allowing you to work in lower light levels.

An f/2.8 lens lets in twice as much light when wide open as an f/4 lens (that's a one stop difference). And ISO 6400 provides twice the sensitivity to light of ISO 3200 (that's a one stop difference too). If you don't understand this talk about 'stops' have a quick read through Photography Basics – Exposure.

So, let's say that today's cameras give the same image quality at ISO 6400 that a camera 10 years ago gave at ISO 800 (that's a three stop difference). Then that must mean that if 10 years ago we needed an f/1.4 lens to work in low light at ISO 800, today we only need an f/4 lens, and can work at ISO 6400.

Badlands diary #3 by Sebastian Fritzon on Flickr (licensed CC-BY-ND) - photo taken at ISO 800 with a D80, released 2006

So at first glance the statement that we no longer need fast glass seems true. We can use a lens with a relatively slow maximum aperture, boost the ISO, and get good results.

However, whether or not you need fast glass depends a great deal on what you photograph, and how you photograph it. The use for high ISO is when the light levels are low, and you want a reasonable shutter speed. This could be capturing sports in a dimly lit arena. Or just taking photos handheld at night, without having the shutter speed so slow that you get blurry images from camera shake.

If you don't take photos in low light, or you do but are happy to use long exposures, then the ability to use high ISOs with modern cameras is not going to be useful to you. Fast glass does more than just gather large amounts of light. If you needed fast glass before for its other benefits (I'll go into these other benefits later), you'll still need it now.

But it's very possible you didn't need fast glass before and still don't need it now. For example, most landscape photographers are quite happy to work at the base (low) ISO of their camera and use a lens stopped down to f/8, with whatever shutter speed is necessary for a good exposure. It's true that they don't need fast glass, but it's down to the style of shooting rather than the availability of good high ISO quality on modern cameras.

Pettico Colour. by Jonathan Combe on Flickr (licensed CC-BY) - long exposure taken at f/8 and ISO 100.

What's wrong with fast glass?

Before we look at some reasons why you may still want fast glass, despite the high ISO capability of modern cameras, let's look at some of its problems. If your only reason for wanting fast glass is to shoot at reasonable shutter speeds in low light, then slow glass plus a good high ISO capable camera may well be a better choice.

- Price

When comparing a specific focal length lens, the larger the maximum aperture value of the lens (the faster the glass), the more expensive the lens is. For example, looking at Canon's 50mm models: The f/1.8 model is around $125, the f/1.4 around $400, and the f/1.2 model around $1,550. So using a slower lens you could save quite a bit of money.

- Size and Weight

A larger aperture requires larger glass elements, and so fast glass can be quite big and heavy. A slower lens can be quite a bit smaller and lighter.

- Filter size

As part of the size, because fast glass is usually quite large, it means that it also has a large sized filter thread. Large filters tend to cost quite a bit more than smaller filters (as well as taking up more room in your bag).

- Zoomability

The fastest glass will always be fixed focal length prime lenses. Because they have a fixed focal length, they are easier to design with a fast maximum aperture than zoom lenses.

However, if you don't need fast glass, then instead of using several fast prime lenses, you can use a single zoom lens instead. It will be more convenient as you don't need to change the lens when you want to change the focal length. For example, rather than the 24mm f/1.4, 35mm f/1.4, and 50mm f/1.4 lenses, you could replace them with a 24-70mm f/4 zoom lens.

In a similar way, if you previously would have used a fast zoom lens, such as a 24-70mm f/2.8 lens, you could instead replace it with a slower lens that has a much greater zoom range, such as a 28-300mm f/3.5-5.6 lens.

- Image Stabilization

Because fast glass needs large, heavy lens elements, it is less likely to feature image stabilization than slower glass. This is because the image stabilization works by moving the glass in the lens to counteract vibrations, and carefully moving a large heavy piece of glass is more difficult than moving a smaller lighter piece.

This can actually result in a slow lens that features image stabilization being better for handheld low light photography than a faster lens with no stabilization. This does depend on what you shoot though - image stabilization will correct for movement from camera shake but not for movement of your subject.

Why fast glass still has its place

As I mentioned earlier, there are several reasons why fast glass is still a good choice for many photographers. Let's look at these reasons now.

Shallow Depth of Field

Probably the main reason why people buy fast glass is not because they want to shoot in low light. Rather, it is the shallow depth of field fast glass can give, resulting in creamy out of focus backgrounds.

Bergamo - red leaves by Susana Fernandez on Flickr (licensed CC-BY-ND)

Having said that, I do think many photographers overplay the difference slightly faster glass makes. Yes, an f/2.8 lens will produce more background blur than an f/4 lens. But f/4 may well produce enough blur for most people, and certainly a lot more blur than the phone photos most people are used to seeing.

There are plenty of portrait photographers who tend to stick around f/8 to get all their subject in focus, with great results. There's no rule that portraits must be shot at as wide an aperture as possible.

Image quality

This isn't a strict rule, but you'll generally find that faster lenses have better image quality than slower lenses. Because fast lenses are typically premium lenses, the manufacturers try to eke out as much image quality as they can. Whereas with consumer zoom lenses, the quality just needs to be 'good enough'.

This is even more true when you consider that most lenses are at their best stopped down by a couple of stops. So an f/2.8 lens will very likely perform better when stopped down to f/4 than an f/4 lens shot wide open at f/4.

Very low light

For very low light photography, for example photographing the stars at night, the high ISO performance of modern cameras is certainly a boon. But that doesn't mean that fast glass can't help you get even better results.

Milky Way by John Fowler on Flickr (licensed CC-BY) - f/2.8 and ISO 6400

Using fast glass either allows you to use a lower ISO value, thus reducing image noise. Or you can use a faster shutter speed - useful for preventing star trails when photographing the stars, or freezing a moving subject such as sports players or wildlife in low light.

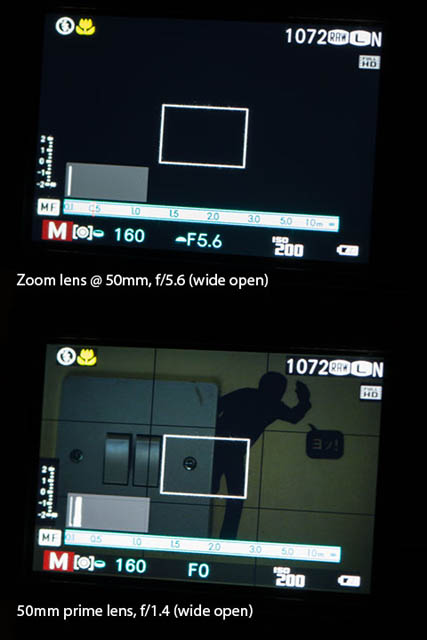

Better low-light autofocus

Because faster glass lets through more light to the camera, this can make it easier for the camera to autofocus in low light. I say can, because it depends a lot on the lens. But if you're using, say an f/2.8 lens in low light, it will very likely focus quite a bit faster than an f/5.6 lens in the same conditions.

Brighter viewfinder

Fast glass can result in a brighter viewfinder, which can be very useful when photographing in low light. However, there are a few caveats. If you're using a camera with an optical viewfinder, the camera may need to be fitted with a focusing screen designed for use with fast glass. Most DSLRs use a focusing screen that shows no difference between lenses at apertures of f/2.8 or larger - an f/1.4 lens would give the same view as an f/2.8 lens.

If you're using an electronic viewfinder (or the camera's rear screen), then using fast glass normally won't affect the brightness of the image at all, unless you are in an extreme low light situation (see example below). But using a fast lens can make the image less grainy, or refresh the view faster in more standard low light situations. However, this is only if you are shooting with the lens wide-open, or have your camera set not to preview the actual exposure.

In a very low light situation a fast lens can mean the difference between a black screen and at least being able to see something on the camera when trying to compose your image.

To sum up, for some people it will be true that the high ISO capability of current cameras means they don't need fast glass. For other people they never needed fast glass because they never shoot at high ISO anyway. And for still others, they do still need fast glass because they need its other benefits (such as shallow DoF), or are pushing the boundaries of what's possible for low light photography.

What about you? Do you like fast glass for smooth defocused backgrounds? Or do you prefer the smaller size, weight, and cost of slower lenses?

I like both fast and slow glass fir all the reasons you pointed out…by having both prime fast and slow zoomies I can compose anything I want…it’s only money…